| Salvadorans

Take Gang Culture Back to Homeland

Text and Photos by Douglas Engle

|

||

|

Home click on each photo for a larger version

|

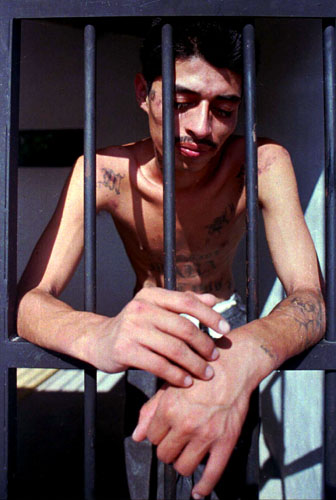

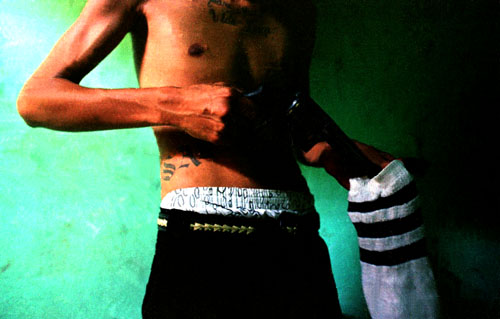

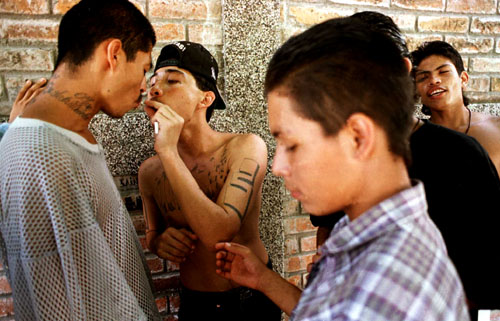

SAN SALVADOR, El Salvador--

Mara Salvatrucha 13 gang member Demonio hangs his hands through the bars of his jail cell and wonders what might happen to him. People have been sent to Mariona, El Salvador's worst prison, for lesser offenses. "I'm a total disaster," he said. "I feel like a total disaster." The police are always looking for an excuse to lock someone like him up. Fortunately he avoided the fate of fellow MS13 gang member ozzy, who was beaten to death within minutes of entering the prison. his crime was throwing rocks, and Demonio helped carry his coffin to the grave. El Salvador, recovering from a bloody 12-year civil war, is facing a crime wave of unprecedented proportions. Bank robberies, shootouts and trafficking of drugs, weapons and stolen vehicles, as well as petty crimes, are overtaking the Central American nation. Ironicly, since the rebels and army stopped shooting at each other in 1992, most Salvadorans say they are more afraid now than at any time during the war. At least the sides were de fined then, they say. Recent Figures released by the Attorney General's office show that the homicide rate had FALLEN in 1995 to 7,877 murders, or about 21 per day, from the 1994 total of 9,135, about 25 per day. Both figures exceed the 6,250 average yearly deaths, or about 17 per day, during the war. "Gangs and criminals are increasingly bloody and dangerous," said Jorge Figeac, head of the prosecuting department of the Attorney General's office. "They act out of rage on their victims. Now, not only do they rob, they murder to avoid charges and possible capture. But attention is overwhelmingly focused on gangs, which have proliferated since the end of the war, when some one million refugees who left for the U.S. during (and before) the war began returning. They bring with them customs and values, good and bad, learned there. Gang Grafitti is everywhere, and after Coca-Cola, gangs appear to be the most visible import from the United States. The estimated 10,000 gang members here, although no angels, make a convenient, imported scapegoat from the ills of the nation. It is easy to blame everything on the gangs. After all, they ARE criminals. But "the government doesn't want to face the fact that they are the ones making the country go to hell," said one member. "They think that it is all imported. It's not. Kids have always been rebellious." Gang members say the rich, not them, are the ones controlling major traffic of drugs, weapons and stolen vehicles. Most likely, gangs play a part in the big picture, as hired stand-ins to do the dirty work. "The mafia organizations that steal cars, move narcotics and traffic in children are using the gangs for these activities now," said Rodrigo Avila, Chief of the National Civil Police (PNC), a creation of the peace accords. "They are paid to be the muscle for operations, they are organized, and we have no structure to combat them. They kill each other without even blinking, and because most of them are underage, we can't hold the ones we catch for more than six hours." The police certainly have their hands full. Combating escalating crime while respecting human rights, the basis of their creation, seems like an impossible task. Pressure from government and business leaders and internal corruption only makes the situation more critical. In one case of January 1996, a group of criminals was tipped off to an operation designed to capture them. When dozens police made their move, including the elite ninja-like Police Reaction Group (GRP), only two criminals were found. The head of the operation suspect that a local judge tipped them off. PNC Deputy director of operations, Ronaldo Garcia said that their plan is to increase troop strength and educate the public to participate in crime solving. As far as anyone knows, no major arsenals of weapons belonging to gangs has ever been found. They have weapons, but not arsenals. Major weapons discoveries have been made though, but not in San Salvador's impoverished working class suburbs, where gangs thrive. Last year police found dozens of M-16 and AK-47 assault rifles, Uzi submachine guns, anti-tank rockets, grenades, bulletproof vests and more during a raid on the Benedicto Band house in the posh Escalon neighborhood. Another is the Walter Auerbach case. Auerbach headed "probably the best organized criminal group in the country" according to police officials. They say he basicly ran a dealership for stolen cars and has links to international car theft rings. He was caught driving a car stolen in Guatemala with false papers which, for some unknown reason was not detected at the border. His home, also in Escalon neighborhood, was also seized. Francisco Valladares, AKA "demonio," 22, has been in the Mara Salvatrucha 13, a gang started in Los Angeles in the 1970's by Salvadoran immigrants, since he was 12. That is where his parents took him whe n he was five and later began stealing cars. Joining a gang in LA was not difficult since he had two uncles in other gangs. "They were pushing me to get into their neighborhood [gang], but I didn't. I got into MS." Since then, he estimates he has spent a total of eight years in proson or juvenile detention. For his last sentence in the U.S., "I did a little burglary and car theft. That's when i got caught." Later authorities found out he shot a man. "He was talking shit to me. I took out a gun and said if you don't leave I'm gonna shoot you." He didn't leave. "So I shot him twice," in the legs. When parole came up, although a legal U.S. resident, he was deported to El Salvador, a country he hardly knew. In the U.S., the justice system is swamped with cases like his. That, included with an anti-immigrant sentiment, only seems to legitimize the the policy of deporting social undesirables which the U.S. government itself helped create by intervening in El Salvador's civil war. So Demonio and hundred like him bring the gang culture of crime, drugs and tattoos to El Salvador and teach it to eager adolescents who look up to them in awe. His first days back were hard, he remembers. People laughed at the way he spoke and he felt lonely. He has no immediate family here, and gang life is different than in LA. Here, he says, gang memb ers are less united don't help each other out as much. For example, when he was released from jail after his car accident, other members told him they had thought of taking a collection to pay his bail, but decided against it. reasoning they should buy tamales instead for his funeral. The U.S. government's quasi-colonial relationship with counties like El Salvador in which repressive governments werre once supported and where now neoliberal economics promoted has created the conditions which make people like demonio join a gang. His family left because there was no opportunity to improve their lot in life. The civil war was simply another reason for thousands of others to leave or for demonio's family to stay away. The county's trial with democracy, which allows more tolerance of ideas than under authoritarian regimes of the past has also contributed to the rise of the gangs. The FMLN, once a guerilla army, is now a leagal political party. Former enemies now battle it out on the floor of the National Assembly. Not too long ago, to think that mortal enemies of the salvadoran front of the Cold War would be part of the same government was as absurd as the thought of the fall of the Berlin Wall. The fragile seed of democracy planted at the end of the war IS giving fruit, although slowly, o f new ideas and customs. it is almost inevitable that gangs proliferate here. The job future is bleak for youths growing up in El Salvador's impoverished areas, where parents, too busy in the daily struggle to make ends meet, have little time for their children. Gangs take the place of family. Brothers Pollo, 15, and Gizmo, 17, were certainly impressed. "I went to the first meeting and there were quite a few "vatos" from Los Angeles. It was scary to go to one of those first meetings. It was the first time i had seen a bunch of tattoos and all. Wow," said Pollo. They way they swagger when they walk, their defiant slouch, they way they use english slang and their droopy dress are all too cool to resist. Especially when life has little else to offer. Gangs offer what family and social institutions cannot: a family, pride, role models and most of all, something to do. "Los Naranjos [neighborhood] has been real original," said Gizmo. "when I go there, it's like my home. I feel that environment, that warmth." Pollo and Gizmo, who joined the MS last year, haven't seen their father for three years. he left with their mother to work in the U.S. eleven years ago. She has since come back, but plans on going again to make money to send back to them so they can go to school again. "There is no opportunity here," she said. "I plan on he lping them alot. going away I can do it. If i don't go i cannot do it. Here i cannot." She says the two joined the gang because of peer pressure and for "adventure." "Their buddies put ideas into their heads. They dont even know what they were doing. They were just kids. When they finally realized it, they were sunken in disgrace. Tatooing yourself is a disgrace because now who is going to give them a job? Now they are something on the edge of society." "Children need to feel love," said one member. "Humans are social animals. If they dont get it at home, the look somewhere else." Psycologist William Ivan Lopez says the Salvadoran common criminal is between 18 and 35 years old, comes from broken home and uses drugs or alcohol. "Because of the war, some people became used to living in a conflictiv e situation in every move they make. And learning from violence was a way to survive and live together in those 12 years. The result is that violence moves into the post-war and becomes a way of survival for some people." "This means that the war was most costly to young people. They suffered the biggest impact because both sides fed off them. they were the most traumatized," he said. Demonio, at 22, is old for a gang member and wonders about his future. He would like to shape up, but for someo ne who has spent most of his life in crime or prison, it is hard to change. Social norms work against gang members too. In El Salvador most people are simply scared to death of anyone with a tattoo. After suffering sever blows to his head during a fight with a member of a rival gang, Demonio spent several days of excrucuating pain on a bed in the public hospital. He had a blood clot in his head and was delerious. Words came out in a jumble and he could not remember the simplest detail. but because of his tatoos, he haid to wait for attention. Care at the hospital is already poor, and for someone with tattoos, even worse. "They like to see [attend to] everybody but for people like us they are wimps," he said later. "I fucked up with all these tags [tattoos]...nobody gives you a job. They don't give you shit," complained Demonio, who says he may have the visible ones, on his face and neck, removed. He even went to a clinic for an estimate. But getting rid of tattoos does not mean leaving the gang. "It means i want a life of my own." "We get to a point and we know we are getting

old. It doesn't look good." said one member. "when you are young you don't

care. A lot of homeboys [gang members] kill themselves for that.

They all want to go out in glory, but what happens when they dont k

ill

you?

Douglas Engle produced this story while working for the Associated Press In El Salvador.

Copyright © douglas engle 1996 |